Molly and Everard Findlay

Molly and Everard, you have backgrounds and decades of experience in creative industries — styling, set design, and studio art for Molly, and global strategy and brand development for Everard. Is there a project you are working on together at the moment?

Currently we are working together on an initiative called Planetary Self, bringing scientists, artists and innovators together across silos to collaborate on unique works. The people involved are incredible, and come from very different walks of life. Our most recent cohort connects Brown University Professor and Simons Foundation fellow Dr. Stephon Alexander with the globally beloved seminal techno group Underground Resistance.Their exploration centers around light and sound – the Wavelength. We are very excited about finding ways to come into right relationship with the planet, the community, and the self, centered on the idea that each person has an inalienable right to be on Earth. We provide pathways for the individual to be attached with the collective in practical, grounded, in-person ways. We are currently developing the physical spaces for Planetary Self Institute to foster these relationships and collaborative works in Detroit, Michigan, Gasparee Island, Trinidad and NYC.

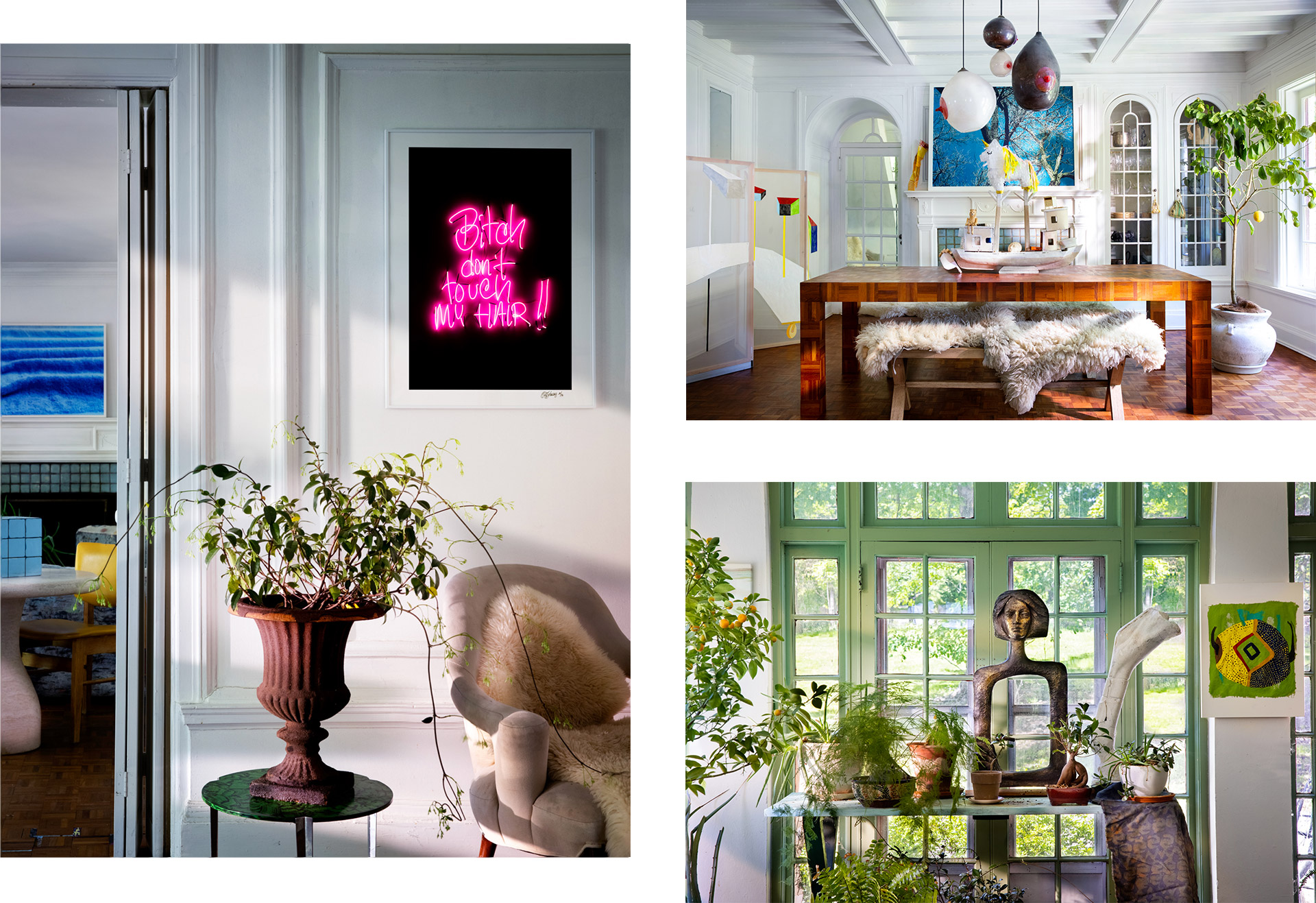

What’s your priority when it comes to collecting art?

The relationship with objects is a profound one – for us the priority usually rests on the people making the art. Having these objects in our midst is like an ongoing line to the hands that made them. Most of the works we have come from friends or colleagues and hold special value to us beyond their intrinsic value.

What’s the most sentimental piece you own?

The most sentimental piece we own is a family portrait painted by our daughter Eleanor when she was around 3, or the large portraits Molly did of our family.

What’s a work or place that inspires you?

We are very inspired when works conspire to bring people together, or to address some challenge or issue at play in the culture at that moment. The African Bead Museum, conceived by artist Olayami Dabls in Detroit is both a place and a work. His compound of buildings encrusted with beads and mosaic are a touchstone, an emblem for the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the creative spirit to simultaneously activate a space, educate and create awe in the midst of innumerable challenges.

What’s important to you for the spaces you spend time in?

They should be inviting, thought-provoking, humorous, and should not be too precious to enjoy.

What are you looking forward to adding to your collection in the future?

We are interested in focusing more on the landscape, and developing earth-based works or outdoor sculptural works, things that draw people into nature.

“We are very inspired when works conspire to bring people together, or to address some challenge or issue at play in the culture at that moment.” —Molly and Everard Findlay