Detroit—on the other side of the country’s largest municipal bankruptcy—suddenly looks like a good investment. Developer Peter Cummings (OPM 13, 1988) takes us on a tour of the city’s real estate revival

Re: John Rhea (MBA 1992)

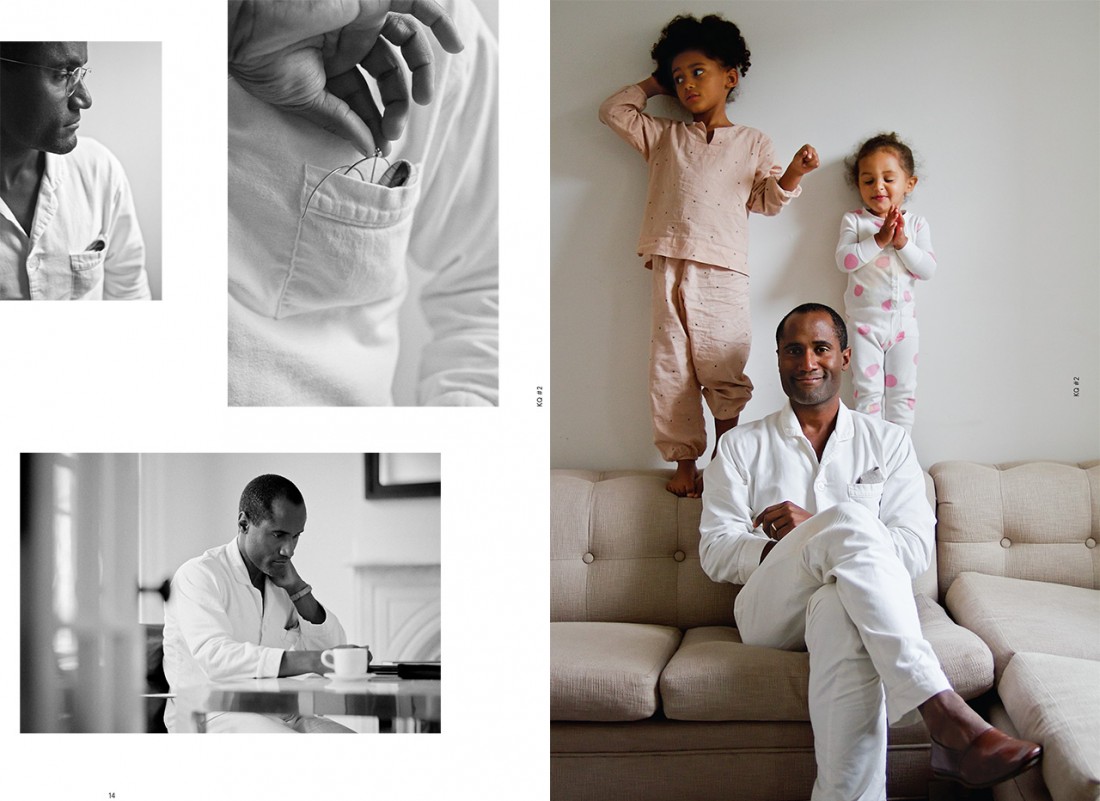

by April White; photographed by Brian Kelly

A trip through downtown Detroit with Peter Cummings (OPM 13, 1988) is part urban planning seminar, part zoning board meeting, and part family history. As the 68-year-old real estate developer navigates the central business district, he sketches an idiosyncratic map of the city—almost three decades of knowledge of what each piece of property used to be, what it could have been, what it is now, and what it might become—laid out along an opinionated time line of Detroit’s highs and lows. And there have been a lot of lows.

Just a few years ago, Cummings was done with Detroit. The municipal government was in disarray, the auto industry was collapsing, the population was plummeting, and business opportunities had vanished. Now he’s back, making big real estate bets that could shape the city’s future. He’s all in on Detroit.

You could say Cummings married into Detroit: His father-in-law was Max Fisher, a pillar of the business and philanthropic communities known as “Mr. Detroit.” Cummings, a Montreal native, and his family moved to the area in 1989 so his children could attend the prestigious Cranbrook schools in the city’s northern suburbs, which his wife, Julie, had also attended.

The Detroit economy was already wavering when the Cummings family arrived. By early 1992, Detroit’s debt rating would be cut to junk bond status. From an investor’s point of view, the city had been a roulette wheel for decades, its fortunes linked tightly to volatile gas prices and the faltering auto industry. From a resident’s point of view, life in a city with inconsistent municipal services and simmering racial tensions could be even more tenuous. While many suburbs prospered, some city neighborhoods were nearly abandoned.

But Cummings still saw opportunity in the struggling city. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, he became a prominent developer, often in partnership with his father-in-law. With Fisher’s encouragement, Cummings developed the ambitious Orchestra Place project, the home of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. By 2005, though, Cummings saw the potential of the city dwindling. The change was partially economic—the city’s credit rating, which had improved by the end of the 1990s, slipped again in the 2000s—and partially personal: Cumming’s children had graduated from Cranbrook and his father-in-law, a friend and mentor, passed away. “In everything I had been doing in Detroit, Max was my partner in a literal sense or a spiritual sense, and a lot of the joy of doing stuff here evaporated when he died,” Cummings says, as we tour the city Fisher helped shape.

Cummings was done with Detroit. Then Whole Foods called.

In 2010, the upscale national grocer—at the gentle suggestion of Michigan Senator Debbie Stabenow—came to look at properties in central Detroit. One of them was a vacant piece of land that Cummings owned on Mack Avenue in Midtown, next to the first project he had developed in Detroit almost 15 years earlier, a surprisingly elegant parking structure.

It took several years and complicated financing, but on June 5, 2013, Cummings watched as hundreds of Detroiters—black and white, rich and poor—gathered in front of the new grocery store. The city’s leaders gave speeches; there were more than a few tears. A high-school marching band played The Temptations’ “Get Ready,” and Cummings and dozens of others involved in the project broke bread to officially open the store. That moment is one Cummings often talks about as “a religious experience.” The Whole Foods store was the type of development—an investment in improving everyday life in Detroit by a national retailer—that people didn’t believe could happen in the city.

This certainly wasn’t the largest or most profitable project Cummings had ever undertaken, but that morning it became one of the most influential for the developer. In the Whole Foods parking lot, Cummings had seen Detroit pride, which he shares. But he also saw something more, something he hadn’t seen in the city in recent years: business opportunity.

Sure, Detroit had made many comebacks in the past half century. At regular intervals, national headlines had heralded the city’s resurgence against a backdrop of dilapidated houses, images now so clichéd as to be their own banal genre—“ruin porn.” But those comebacks never lasted long enough. This moment is different, Cummings says.

Cummings lists the same five points many developers making investments in the city do, starting with the lowest point in Detroit’s financial history: In July 2013, the city filed for Chapter 9; it was the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in US history. “Uncertainty is a horrible constraint for investment,” says Cummings, of the financial chaos prior to the bankruptcy. But when the city emerged from bankruptcy 17 months later, investors took another look. “Now the uncertainty has been removed.”

Add to that the business-minded political changes: Democratic mayor Mike Duggan came to city hall in 2014 after eight years as CEO of the Detroit Medical Center. Add the renewed growth of the US auto industry, which set all-time sales records in 2015 and helped Detroit’s unemployment rate drop to its lowest in 15 years; add the phenomenon that is Dan Gilbert, the billionaire businessman who made an unprecedented investment in the city when he moved the Quicken Loans and Rock Ventures headquarters from the suburbs to the downtown area in 2010; and add urban-dwelling millennials, who see opportunity in Detroit’s relatively inexpensive real estate. Of some potential foreign investors eyeing real estate in Detroit, Cummings says, “They’ve come to the conclusion that investing in Detroit is like investing in an emerging economy without political and currency risk.”

Cummings has formed a new company to manage his Detroit projects: The Platform. The name has many meanings for him. A “plat” is a map, and a “platform” can refer to one’s policies, but most importantly, a platform is something you can build on.