Again In A Great City

June, 2016

Detroit—on the other side of the country’s largest municipal bankruptcy—suddenly looks like a good investment. Developer Peter Cummings (OPM 13, 1988) takes us on a tour of the city’s real estate revival

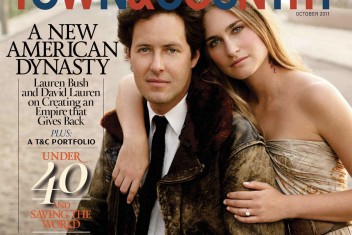

Re: John Rhea (MBA 1992)

by April White; photographed by Brian Kelly

A trip through downtown Detroit with Peter Cummings (OPM 13, 1988) is part urban planning seminar, part zoning board meeting, and part family history. As the 68-year-old real estate developer navigates the central business district, he sketches an idiosyncratic map of the city—almost three decades of knowledge of what each piece of property used to be, what it could have been, what it is now, and what it might become—laid out along an opinionated time line of Detroit’s highs and lows. And there have been a lot of lows.

Just a few years ago, Cummings was done with Detroit. The municipal government was in disarray, the auto industry was collapsing, the population was plummeting, and business opportunities had vanished. Now he’s back, making big real estate bets that could shape the city’s future. He’s all in on Detroit.

You could say Cummings married into Detroit: His father-in-law was Max Fisher, a pillar of the business and philanthropic communities known as “Mr. Detroit.” Cummings, a Montreal native, and his family moved to the area in 1989 so his children could attend the prestigious Cranbrook schools in the city’s northern suburbs, which his wife, Julie, had also attended.

The Detroit economy was already wavering when the Cummings family arrived. By early 1992, Detroit’s debt rating would be cut to junk bond status. From an investor’s point of view, the city had been a roulette wheel for decades, its fortunes linked tightly to volatile gas prices and the faltering auto industry. From a resident’s point of view, life in a city with inconsistent municipal services and simmering racial tensions could be even more tenuous. While many suburbs prospered, some city neighborhoods were nearly abandoned.

But Cummings still saw opportunity in the struggling city. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, he became a prominent developer, often in partnership with his father-in-law. With Fisher’s encouragement, Cummings developed the ambitious Orchestra Place project, the home of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. By 2005, though, Cummings saw the potential of the city dwindling. The change was partially economic—the city’s credit rating, which had improved by the end of the 1990s, slipped again in the 2000s—and partially personal: Cumming’s children had graduated from Cranbrook and his father-in-law, a friend and mentor, passed away. “In everything I had been doing in Detroit, Max was my partner in a literal sense or a spiritual sense, and a lot of the joy of doing stuff here evaporated when he died,” Cummings says, as we tour the city Fisher helped shape.

Cummings was done with Detroit. Then Whole Foods called.

In 2010, the upscale national grocer—at the gentle suggestion of Michigan Senator Debbie Stabenow—came to look at properties in central Detroit. One of them was a vacant piece of land that Cummings owned on Mack Avenue in Midtown, next to the first project he had developed in Detroit almost 15 years earlier, a surprisingly elegant parking structure.

It took several years and complicated financing, but on June 5, 2013, Cummings watched as hundreds of Detroiters—black and white, rich and poor—gathered in front of the new grocery store. The city’s leaders gave speeches; there were more than a few tears. A high-school marching band played The Temptations’ “Get Ready,” and Cummings and dozens of others involved in the project broke bread to officially open the store. That moment is one Cummings often talks about as “a religious experience.” The Whole Foods store was the type of development—an investment in improving everyday life in Detroit by a national retailer—that people didn’t believe could happen in the city.

This certainly wasn’t the largest or most profitable project Cummings had ever undertaken, but that morning it became one of the most influential for the developer. In the Whole Foods parking lot, Cummings had seen Detroit pride, which he shares. But he also saw something more, something he hadn’t seen in the city in recent years: business opportunity.

Sure, Detroit had made many comebacks in the past half century. At regular intervals, national headlines had heralded the city’s resurgence against a backdrop of dilapidated houses, images now so clichéd as to be their own banal genre—“ruin porn.” But those comebacks never lasted long enough. This moment is different, Cummings says.

Cummings lists the same five points many developers making investments in the city do, starting with the lowest point in Detroit’s financial history: In July 2013, the city filed for Chapter 9; it was the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in US history. “Uncertainty is a horrible constraint for investment,” says Cummings, of the financial chaos prior to the bankruptcy. But when the city emerged from bankruptcy 17 months later, investors took another look. “Now the uncertainty has been removed.”

Add to that the business-minded political changes: Democratic mayor Mike Duggan came to city hall in 2014 after eight years as CEO of the Detroit Medical Center. Add the renewed growth of the US auto industry, which set all-time sales records in 2015 and helped Detroit’s unemployment rate drop to its lowest in 15 years; add the phenomenon that is Dan Gilbert, the billionaire businessman who made an unprecedented investment in the city when he moved the Quicken Loans and Rock Ventures headquarters from the suburbs to the downtown area in 2010; and add urban-dwelling millennials, who see opportunity in Detroit’s relatively inexpensive real estate. Of some potential foreign investors eyeing real estate in Detroit, Cummings says, “They’ve come to the conclusion that investing in Detroit is like investing in an emerging economy without political and currency risk.”

Cummings has formed a new company to manage his Detroit projects: The Platform. The name has many meanings for him. A “plat” is a map, and a “platform” can refer to one’s policies, but most importantly, a platform is something you can build on.

Any tour of Detroit’s future begins along Woodward Avenue in the central business district—“Dan Gilbert’s duchy,” Cummings says, as he navigates the city behind the wheel of a silver Chrysler minivan, his Detroit-made Shinola watch glinting in the sun. Gilbert controls more than 80 commercial properties in the neighborhood, and it is his employees—more than 12,500 of them at Quicken Loans alone—who flood the streets at lunchtime, use the new bike share program, live in the renovated lofts, and anxiously await the completion of the light-rail through the city.

As we head toward the waterfront, we circle the small Campus Martius Park. The city’s mile road system originates here; 8 Mile is eight miles away. In the 1990s, when the park was first conceived, it was a signal of a future for the neighborhood; Cummings sat on the board that designed it. Suddenly, the Renaissance Center pops into view, a self-contained city of seven gleaming skyscrapers built in the 1970s. A relic of a time when the Ford family shaped the city, it was once home to the Ford Motor Company. The tallest of the buildings is now topped with the iconic blue GM symbol.

We’re on our way to see something else entirely: a nearby parking lot. From this vacant piece of pavement, Cummings can see one piece of his father-in-law’s legacy and a hint of Detroit’s future development. Max Fisher and his partner Al Taubman were the first to build apartment towers along the Detroit River, an effort to turn the city’s industrial waterfront into a residential attraction. Today, the popular Detroit RiverWalk reaches along the shoreline, and more residential development is under way. Cummings bought the Riverfront Towers complex from Fisher and Taubman; he and his wife lived there for several years before selling the complex. He still owns this adjacent parking lot, which he hopes will be part of a redevelopment project when the nearby Joe Louis Arena, where the Detroit Red Wings hockey team plays, is demolished. “This is an area that eventually is going to get developed. It will be largely residential and hospitality, with entertainment-oriented retail,” Cummings says. He dispenses this optimistic wisdom in a low rumble and cranes his neck to see the top of each building, as if still impressed by the heights they’ve reached.

Now it’s on to “Ilitch country,” as Cummings calls it, downtown’s sports and entertainment district. The Ilitch family, the founders of Little Caesars pizza chain, owns the Red Wings and the Detroit Tigers baseball team. The Tigers stadium is in Ilitch country, more commonly known as Foxtown, and the new Red Wings arena is planned for the area. The family also has the Fox Theatre, a casino, and numerous other real estate investments in the area.

That’s an important quirk of the city’s tumultuous economic history. Detroit was long a company town, and then, when there was no one else—not even the city—investing in Detroit, those who did became the new kings and queens of their neighborhoods. Henry Ford II shaped the Renaissance Center. Max Fisher transformed the waterfront. Now developers like Gilbert and the Ilitches have an outsized impact on the way their particular neighborhoods develop, as do local philanthropic foundations, which have stepped into the void left by the municipal government. The responsibility that comes with such power is something that Cummings will be forced to consider with his biggest investment in Detroit to date: the Fisher Building. (No relation to Max Fisher.) In New Center, three miles northwest on Woodward Avenue from where our tour started, the 28-story structure rises from among low-slung concrete buildings. Will this become “Cummings land”?

The Fisher Building has been an icon of the Detroit skyline for almost 90 years. The massive building, spanning a city block, is clad in marble, some 325,000 square feet of it. More than 40 types of the stone were imported from around the world for the facade and the building’s vaulted three-story lobby. The windows—1,800 of them—are rimmed in bronze. Its roof was once leafed in gold; the nickname “The Golden Tower” lingers, though it has been covered in green terra-cotta since the end of World War II.

The cost to construct the building in 1928 was $10 million, $135 million in today’s dollars. Last June Cummings and his partners—including former NYC Housing Authority chairman and Detroit native John Rhea (MBA 1992), managing partner of New York–based RHEAL Capital Management—purchased the building, plus the nearby Albert Kahn Building and 2,000 parking spaces, for just $12.2 million at auction. Rhea’s interest in Detroit and the New Center neighborhood is mainly residential, but when the Fisher Building came on the market, he shared Cummings’s vision: “If Fisher is not managed right, and the redevelopment of it isn’t thoughtful, it will actually cause the rest of the redevelopment of New Center to under perform,” he says. The team considers themselves stewards of the neighborhood’s redevelopment, starting with the Fisher.

Cummings surveys the lobby of the Fisher, as a rush of well-dressed Detroiters head into a matinee at the 2000-seat Fisher Theatre. “It’s really absolutely extraordinary,” he says of the building. And from here, it is. The lobby looks like a museum piece, its pendant lights bright and its bronze polished to a shine. But the rest of the structure is not as well maintained. Cummings and his partners expect to spend as much as $100 million to rehabilitate the Fisher and the Kahn.

On this day, it’s been six months since the auction, and though the pieces are still coming together, Cummings has a clear vision for New Center: a combination of mid-level local and national retail and residential properties, a type of high-density development rarely seen outside the city’s central business district. This neighborhood looked like that in the 1920s—and it’s also what new urban living looks like, with a twist. General Motors once anchored New Center. Now, with the development of the light-rail just blocks away, there’s a possible future where even Detroit could become less dependent on cars.

National retailers are buying into Cummings’s vision: a leading home-furnishing retailer is eyeing a ground-floor space in the Fisher and various operators are considering a boutique hotel in one wing of the building. Cummings and his partners were considering luxury condos in the upper reaches of the building, but they worry that Detroit may not yet be ready for the prices such prime real estate would command. For the Kahn Building, Cummings is working on a deal with another leading home-furnishing retailer, for a space on the first floor, and he also plans 165 residential units on the upper floors.

Cummings drives around the New Center and nearby Tech Town neighborhoods, pointing out projects he’s working on. At 3rd and Grand, he gestures to a parking lot. In his mind’s eye, he sees a new mixed-use building, with 230 residential units atop 20,000 square feet of retail space; the $50 million project is expected to break ground later this year. And the best part is, he’s not the only one here: Wayne State University, the Henry Ford Health System, and the State of Michigan all have properties in the neighborhood. That’s one of the big attractions for Cummings. His vision for New Center and for Detroit is “a more granular, more organic, more diverse source of development visions and capital.”

Cummings made another purchase about the same time that he and his partners bought the Fisher Building. Comparatively, it was a small investment—just $80,000—but it is in some ways a riskier one. Cummings wants to show me the property, but first he has to set his GPS. It’s the only time he’s needed to use one, and even with the guidance, there’s a moment we almost end up in Canada.

We’re headed to Brightmoor, a neighborhood on the northwest edge of the city. It is also known as “Blight More.” Although it is not quite seven miles straight from Campus Martius Park, it is a world untouched by the development reshaping the center of the city. As we near our destination, Cummings notes that by car Brightmoor’s distance from the revitalization in Detroit’s business district is just about the same as the distance from downtown St. Louis to Ferguson, in that forgotten ring between a city’s center and its wealthy suburbs.

Brightmoor looks the way outsiders have come to imagine Detroit: both empty and overrun, with heartbreaking glimmers of hope. Even residential streets that appear predominantly abandoned have at least one house with a well-maintained garden or lovingly hung holiday decorations. Here, at the corner of Grand River and Lahser, Cummings purchased five commercial properties: a restaurant, a parking lot, and a vacant storefront among them. Like the Fisher Building, these properties have both history and potential, but it is hard to see that through the vacant building’s grayed plywood.

Cummings doesn’t have a clear vision for these properties yet. He’s aware that this investment could look like an outsider trying to make a buck on the back of poverty or trying to dictate the development of a neighborhood he can barely find, but Cummings has come to community leaders with some pedigree: His wife’s family foundation has been active in offering social services in the neighborhood for almost a decade. He has contributed the properties to a foundation and has engaged community leaders in creating a vision for their redevelopment.

What Cummings does know for sure is that something needs to be done in neighborhoods like Brightmoor, that the city can’t thrive without that. That’s the biggest question that comes with renewed interest in Detroit real estate: Will development dollars revitalize the city for the many or for the few? “There’s so much attention and so many resources that want to come in to the city, you’ve just got to make sure that some of that attention gets directed to the places where people tend to get forgotten.”

Cummings doesn’t see the same business opportunity here in Brightmoor that he sees in Midtown, but he sees a developer’s responsibility to invest in Detroit’s future: “I’m a real estate developer: Every problem has a real estate solution.”